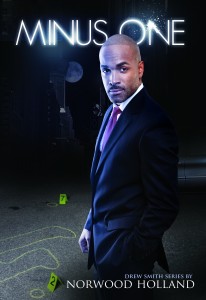

A conversation with Beverly Jenkins

September 3, 2012

Beverly Jenkins has received numerous awards, including three Walden Booksellers Awards, two Career Achievement Awards from Romantic Times magazine, a Golden Pin Award from the Black Writers Guild. In 1999, Beverly Jenkins was voted one of the top 50 favorite African-American writers of the 20th century by the African American Literature Book Club, the nation’s largest African-American Book Club.

Beverly Jenkins has received numerous awards, including three Walden Booksellers Awards, two Career Achievement Awards from Romantic Times magazine, a Golden Pin Award from the Black Writers Guild. In 1999, Beverly Jenkins was voted one of the top 50 favorite African-American writers of the 20th century by the African American Literature Book Club, the nation’s largest African-American Book Club.

[You can listen to this interview by clicking on this link Beverly Jenkins]

Norwood: It’s a pleasure to speak with you. I recently read Night Hawk, and not only did I find it a fascinating and titillating read, but also a lesson in history. As a sidebar, after meeting you in April, I came home and my aunt who’s a history buff, asked me what I reading. I recommended that she read Night Hawk. She went online, downloaded it on her Kindle, and she read Night Hawk, and she has since read everything that she can her hands on.

Beverly Jenkins: That seems to be a common thing, people get hooked.

Norwood: It seems as though you’re addictive.

Beverly Jenkins: I hear good stories. You get African-American history in a user-friendly kind of a format, and you get a great story. So what more can you ask for in a body of work or in a book?

Norwood: Let’s talk about your writing journey. What was that seminal moment when you decided you wanted to be a writer, or did you always know you wanted to be a romance author?

Beverly Jenkins: I never wanted to be a writer. This is something I just sort of stumbled into. I always knew I could write. I started out — I tell people I’m a proud product of Detroit public schools. I was the editor of my elementary school newspaper in the 4th grade, I was 8-9 years old — avid reader all my life. My only goal was to work in a library. I loved books — read, read, read, read, read — from a family of readers, my mom, my dad, my sisters, my brothers.

I was working on a story — I was working at the reference desk at what used to be Park Davis Pharmaceuticals in Ann Arbor, and there was a woman there who was a member of the Romance Writers of America. I showed her my story. She was trying to get published also. I wasn’t trying to get published, I was just writing the story for me because there was no real African-American love stories out there at that time. So I showed this to her, and she says, well, you really need to get this published; and I’m like, yeah, right.

I read everything. I read romance, I read fiction, non-fiction, I’m a big fantasy reader and lots of non-fiction. So I hadn’t planned on getting this published, and I didn’t think that I would be published because of the way publishing was structured at that time.

I said to my girlfriend, Laverne, and to make her shut up, I did a little bit of research and ran down Vivian Stephens, who is a big-time editor at Dell back then, she was a big romance editor. She had gotten out of publishing, and she was doing agenting. So I sent her my pitiful little excuse for a manuscript, and she called me back at work maybe three or four days later and said that she wanted to represent me.

So submitted it — I got enough rejections probably to paper my house. Then finally, Ellen Edwards, who was the editor at Avon Romance, which is probably the largest and most successful romance house back then — this was the early ’90s/’94 — said, yes. So, 30 books later, I’m still with Avon — great editors, great house.

So, that’s sort of the short version of my journey.

Norwood: You seem to have taken a road that is pretty much compatible with being a writer — you’re well read. For those who read a lot, writing seems to come naturally.

Beverly Jenkins: Yeah, I do a lot of writing workshops. I travel all over the country doing writing workshops, speaking on 19th century African-American history and, of course, romance too. One of the things that I try and promote among writers is that the person who reads the most books wins; because the more you read, of course, the better your vocabulary, but you also get a sense of voice. Voice being — for those who are not sure what voice is — is nothing more than how you sound on paper. You can develop that voice by reading other voices. It’s a blessed life, it really is a blessed life.

Norwood: It’s only through writing that you come into your own voice. So, let’s get to historical romances; specifically, African-American historical romances. Your research — what’s your methodology, how do you go about it? First of all, you come up with a plot/a story, or does a story grow out of your research?

Beverly Jenkins: Every book is different. There’s sometimes no rhyme or reason to why this story, as opposed to that story.

Just to give you some background: My mom was black before it was fashionable. I grew up with Langston Hughes and Arna Bontemps and Countee Cullen, and all of the great Harlem renaissance writers and poets. One of my first memories was of her reading me James Weldon Johnson, The Creation. So, I took that background and I used that to paint my stories.

I like to put my stories where black folks actually walked. So, you’re going to get the stories of the Great Exodus of 1879, and the founding of those small black townships in Kansas. You’re going to get stories about Harriet Tubman’s spy group, which a lot of people don’t know that — they know that Harriet helped escaped slaves, but not a lot of people know that she was doing spy work for the Union Army during the Civil War. You’re going to get stories from me from the black and brown outlaws and lawmen of Indian Territory, because we were in all of those places.

So you take that history, and sometimes it comes through the history, sometimes I’ll run across a character that I’ve come across that I want to put in the story. For me, usually the story dictates where I go. I often say that the story doesn’t come from me, as opposed to coming through me (if that makes any sense). I don’t know where these stories come from, you know. I say this often — any time I’m watching football, I’m a very avid fan, and a character taps me on the shoulder and says, write my story — like, who are you, get away from me, I’m watching the game.

So I have characters stacked up in my head, like, planes over LaGuardia. Hopefully, I have enough time in this lifetime to get them all done; if not, maybe the Good Lord will give me a good chance the next time when I come around to finish what I didn’t finish in this life.

Norwood: I hear you.

Beverly Jenkins: But history moves me. History is one of the things I’m most proud of in my writing; because of that history, I’ve gotten to travel all over the country.

Norwood: Well, it’s a very fertile subject, any number of topics/characters that you can draw on. Speaking of characters, Maggie Freeman is in my heart. When I first saw her, I had no problem imagining her to look like Edmonia Lewis — are you familiar?

Beverly Jenkins: Yes, the sculptress.

Norwood: They had of similar biographies, only Edmonia Lewis’ father was Caribbean and her mother was Indian and came from Canada. It occurred to me, there were thousands of women like Edmonia and Maggie.

Beverly Jenkins: Oh yeah, and their stories have not been told. I think that’s one of the things that people appreciate about my writing, is that I’m patching up those holes in the quilt for American history. But in Maggie’s case, she’s sort of based on a woman that I met in Omaha, Nebraska — her name is Maggie Sherman. Maggie is Kaw Indian, and her dad is black — she’s Native-American on her mom’s side. I met her at a signing a few years back, and she was just so appreciative because I’d written about Native-American and black women before. She said, you know, nobody’s writing about me, and I’m so thankful. She was in tears and I was in tears.

She sent me this great letter about some of her background, and how her grandfather proposed to her mother. I said, you know, this is a great, great story. So I named her Maggie, after Maggie Freeman. I knew nothing about the Kaw Indians; you know, you hear about the Sioux and the Cheyenne, you know, a lot of the plains Indians because of the movies and all that from Hollywood — but you very, very rarely how about many of the small tribes. The Kaw are what the French and the European settlers called the Kansas Indians. So just a fascinating history.

Every time I turn around, you know, somebody’s sending me stuff, or I’m meeting somebody with a great background. It’s all good.

Norwood: Well, before we get too far into it, can you give the us a brief synopsis of Night Hawk and Maggie Freeman.

Beverly Jenkins: Night Hawk is — I’m like four books past that book now, so I’ve got to open up the brain and stuff. Ian Vance, he first showed up in a book called — him and Jesse Rose, back in the mid-’90s. I call him my gun-toting, Bible-quoting bounty hunter. He’s a bounty hunter in that first book. The women seem so taken with him, that for the 10 years after that book was published, I kept getting letters and emails and all that about when is the — he’s called the preacher — when’s the preacher going to get his book.

Finally, he got his book, Night Hawk. We knew that he was black and Scottish — his father was a black Navy English seaman, and there were many of them, and his mother was a Scottish woman. Just like sailors all over the world, they leave babies behind, and the black Navy guys, the black English guys were no exception. There are some who’d say — historians who say that that’s the origination of the word, “black Irish” came from was from these seamen leaving these babies.

So he eventually makes his way to the United States, and he has a degree and he’s a lawyer; of course, at that time in the mid-1860’s, 1870s, 1880s, he is not allowed to practice his craft. So he comes across another group of my characters who are black Seminoles, and they are train robbers in response to America’s dealing with black Seminoles down on the coast of Mexico and Texas, and they started robbing trains to feed their families. So he runs into them on a train ride, and winds up hanging with them for a good 8-9 years, robbing trains and doing all that.

He becomes a bounty hunter when his wife is murdered by a different set of gang people, outlaws. So he is on his way, he’s going to give up being — he’s tired of being a bounty hunter, he’s going back to his ranch in Montana — and on the way, runs into Maggie, who is being arrested for something that she did not do. He has to escort her from Kansas to jail in Denver.

Their story, as they get to know each other, and she’s wild — I mean, she’s tough, she’s been on her own since age 12 — and the love story that results from that. I had a great time writing it.

Norwood: Now, Maggie Freeman is a strong, independent black woman, but what is it about Maggie Freeman that your readers identify with?

Beverly Jenkins: I think they have a tendency to identify with all of my women. You know, you’ve got that strength, also the vulnerability; you have that sad story, but you also have the hope that the future will be better, which is, I think, a tenet of our African-American history. The ancestors did not dwell on the old “woe is me” kind of thing; they just said, okay, well we’ve got these lemons, so let’s make lemonade. I think Maggie is a very, very good example of that.

I liked her in the sense that she was not your typical — you know, some romance women write, you know, they’re all virgins — some of my women are not.

Norwood: Well, Maggie’s had a difficult time.

Beverly Jenkins: If you read my body of work, most of these women have not been coddled. As Langston Hughes says, “Life is not a crystal stair.” These women have not had crystal stairs. That, to me, speaks to the African-American condition of black women coming up in the 19th century.

Norwood: I think that answers my question — they’re not privileged.

Beverly Jenkins: But because they’re not, does that mean that they don’t deserve love? One of the things that I had to deal with when I first starting writing was African-American women did not read romance. I understand why because we were not represented in any of the stories. If we were represented, we were this like theater, we were in the back holding spears or something. So, bringing them to the forefront and bringing their stories to the forefront, has been an eye-opener for a lot of women. They can’t get enough, just like your aunt.

Norwood: It’s a billion dollar industry now.

Beverly Jenkins: Romance sells more books than mystery, science fiction, or westerns combined.

Norwood: I read that.

Beverly Jenkins: We pay the bills, we keep the lights on at all these publishing houses for all the rest of this “literary” fiction. I’m proud to do what I do, because I write for the masses — so did people like Dickens, and so did people like Jane Austen, and so did people like Melville, who were very pooh-pooh’d when they were first published. But we are the backbone of fiction at the publishing houses.

Laurie Kahn, who was one of the producers for Eyes On The Prize, is doing a documentary right now on romance writers in their communities — it’s called, Love Between The Covers. She minds this community. I mean, she talks about how much money romance generates. The varied professions of these women — some of these women are physicians, some of them are lawyers, some of them are astrophysicists. You know, it’s not that stereotype of we’re all living in trailer parks and we all write with crayons.

I think the documentary that she’s doing is going to be very, very important to bash a lot of those, and poke holes in a lot of those stereotypes that people think romance writers are and romance writing is. She accompanied me and a group of my sister fans, who are now great friends of mine and a lot of my girlfriend, when I celebrated my 60th birthday last year in Charleston, we do history trips. We went down and we saw the slave mine in Charleston, we saw the Boone Plantation — we did all this history, we were there for three of four days — and she was there. I mean, Laurie was there with her crew. My little part of it is called, Where We Walked, which goes back to me putting my stories where black folks actually walked. So, she used our portion as part of her fundraising, and got a very good-sized grant from the National Endowment of Humanities, so that she continued to try and get this documentary filmed.

I think people who have — you know, this is not your mama’s romance, it’s not your mama’s romance novel, it’s not your mama’s romance writers. Women are doing some great, great writing out there — proud to be, proud to be.

Norwood: I think you’re doing a lot to uplift that genre because the literati has, for some time looked down upon romance fiction.

Beverly Jenkins: Like I said, they think we write with crayons. We don’t care — we’re just churning out the books and making The New York Times bestsellers list, and going about our business, and quietly laughing up our sleeves as we go to the bank every month. It’s all good.

Norwood: You’re teaching too, so that’s a nice way to open a lot of women’s eyes about our history.

Beverly Jenkins: Yeah, it’s been a great journey. I’m learning right along with my fans. But I would not be who I am without all the great historians that my stories and my history’s based on — John Hope Franklin, Dorothy Sterling. So yeah, there’s a bit in the back of my books too, so I’ve got a scholarly.

Norwood: I want to talk about your props, because do you get into details about the different scenarios, like the clothing.

Beverly Jenkins: Yeah, you have to be correct. People will write you. There’s a lot of people out there who are historians, who read your stuff. I knew when I did Night Song, which was my very first book, based on the all-black towns in Kansas after the Great Exodus of 1879, that if I was going to present this story to the public, it had to be accurate. So you wind up doing things like, what did they wear, what did they eat, how long does it take a train to go from Denver to Kansas City, where were the railroads, how were black people expected to act in public — all of those little things that all historical romance and historians do when you write fiction — you have to have it correct. I mean, you can’t just make up stuff, because it doesn’t serve your story, it doesn’t serve you as a writer, and it doesn’t serve your readers.

Norwood: Right, that’s one way to get rid of the suspension of disbelief when you come in with your facts all wrong.

Beverly Jenkins: Yeah. They used to call it “playing Goddess”, just moving stuff around. Okay, well, I’m going to do this and just say this. I don’t play Goddess, I don’t move rivers around, I don’t put people in situations that did not exist. I’m going to give you the every day, what people dealt with in whatever setting my stories are based.

Norwood: So grounding your settings in reality.

Beverly Jenkins: Yeah, I mean, you have to if you’re going to have any kind of credibility.

Norwood: I’ve seen some authors who have not done that. When I see stuff that’s clearly historically inaccurate my first reaction is to sling the book across the room.

Beverly Jenkins: Yeah, that’s what my mother called a “wall banger”, you throw it up against the wall. I knew that this being the “first” African-American historical — Sandra Kitt did a book before mine called, Adam & Eva, that came out a few years before Night Song, but hers was — they were slaves. So I knew that if I wanted to do our history as free people, that this book had to be stellar — that was the reason that you had the bibliography in the back, because I was getting all these questions, did black people really do this. You know, are you kidding me? I’m like, you see the bib list, look it up.

I also got pushback from some black people who were saying, well, you know — because I don’t write dialect — people said, well, black people didn’t talk this way. I said, have you read any of the letters, have you read any of the speeches of the 19th century? You know, that whole dialect thing is Hollywood. If you get your history from Hollywood, you don’t know your history. So, you have to be accurate not only with the details, but also with the syntax.

Norwood: Let’s talk a little bit about your technique. Describe your writing process and your revision process.

Beverly Jenkins: Well, I revise as I write. I may do a page-and-a-half, then go out and do something to take my mind away, load the dishwasher or whatever, and then come back and look at it again. If I do that, then I can see the speed bumps. Some people don’t revise as they’re writing; some people just go ahead and write that first draft, and then go back and do it. But I revise as I go. Once it’s turned in, of course, my editor will weigh in, which is great, because I’ve got great editors — I’ve been really, really blessed — I have great editors. She’ll weigh in, and she’ll say, you know, look at this or look at that; most of the time we agree, sometimes we don’t. But my house has enough faith in my writing that if I say, no, I think I’m going to keep that, they’ll go ahead and let me do that.

I am a stickler for trying to get it to sound right to me. You know, I’ve got this thing and it’s crazy, that the Native-Americans when they’re doing a totem, they always say that the totem is already in the tree, it’s just if a carver is intuitive enough to take off the stuff that doesn’t belong there. That’s how I look at writing. The characters know the story, the story’s already on the page for them; but am I intuitive enough and open enough to take out the stuff that’s not supposed to be there, so that the story can come alive.

My characters talk in my head, I carry them around — a lot of writers say the same thing. But I can look at a character after I’ve written and say, that’s not right, there’s no balance, they’re not supposed to speak that way. For me, it’s a gift — for me to say anything else is for lightning bolts to hit my computer. It’s not me, my stories come through me, not of me.

Norwood: I never looked at it like that, but in writing it’s sort of a metaphysical process. I know what you mean — I’ve been there where the characters just sort of take over the story.

Beverly Jenkins: Yeah, and they take you places where you don’t even know. I did a book called, Always and Forever, and this brother was a U.S. Marshall down in Texas, and wound up having to run for his life and leave Texas, his father was killed and all this. So he goes back to try and clear his name, and runs into the people who murdered his father, and he winds up being almost dragged to his death on the back of a wagon. So his family tries to get him out of that town and get into a place where he can heal up. He winds up going into the swamps of Texas — and I’m writing the story, and I’m like, there’s swamps in Texas? I mean, the characters are taking over the story completely. I had to stop, go get an Atlas and look — sure enough, there’s swamps all the way down the Texas/Louisiana border. I did not know this — the characters knew it.

So you have to learn sometimes to trust your characters. I had not planned on writing anything about this swamp, but there were people there that helped him that I didn’t know were going to be in the story.

I love what I do because of the excitement of sometimes not knowing what the story’s going to be.

Norwood: Okay. So writing for you is also a learning process.

Beverly Jenkins: Yeah. One of the great things about Romance Writers of America is that, you know, they can sort of — to codify a lot of stuff. There are two types of writers: There are plotters — people who plot everything from the very first word to the last word, and I have girlfriends who write that way; we also have pantsers — people who write by the seat of their pants — you’ve got sort of a plot, you’re not really sure what’s going on, but you go ahead and write it. I’m a pantser — nothing gives me more joy than having something happen in the story that I didn’t see coming. So, yeah, I’m a pantser, and I love it.

Norwood: Well, thank you for this time.

Beverly Jenkins: You are so welcome.

Norwood: Before I let you go, tell us what’s coming up next. Now, you said Night Hawk was three or four books back.

Beverly Jenkins: Yeah, I’ve done a couple of books since then. I have my Christian Women’s Fiction series, the Blessing Series, which has been an awesome addition to my work. So I have the fourth book came out right after Night Hawk did; the fifth book will be out in 2014. In fact, I got an email this morning from a gentleman who said he’s dyslexic, and he had never read for pleasure, but he was devouring these Blessing Series — that makes you smile when you get up in the morning and see an email like that.

What’s coming up next is my new series set in California — I’ve never had anything actually set in California, characters that come from California. So this is what I call my Big Valley series — we’ve got a mom and three sons — all of these guys will get a book. California’s got great African-American history, so a lot of the history in this first book. One of the big gems is California’s the only state in the Union named after a black woman. So I got to do a lot of the research on Queen Califia, who California is named after, which was fascinating to me because I knew a little bit about it, but I didn’t know all of it.

Norwood: That’s the first time I’ve heard it.

Beverly Jenkins: It’s real interesting, because she’s this — she’s mythical, of course. But it was the 15th century Spanish book about her, and she was an Amazon, and she lived on this island of gold with these Amazon warriors and these battle-trained griffins. People think that when the Spanish first started exploring the new world, they were looking for this island of gold – El Dorado and all that. So, she has come to symbolize — you know, before the big European takeover of Mexico and all that — symbolizing all of the beauty and the productivity and the produce and all that of California. There are murals of her in some of the older hotels in San Francisco. Whoopi Goldberg did a thing for Disney with Whoopi as Queen Califia in Disney World. They tore it down eventually and replaced it with a ride for the Little Mermaid.

But I’ve been able to explore that great history. You’ll have to look her up, it’s amazing. So the book is dedicated to her, and to my original crew in California. So lots of stuff to come.

Norwood: I think you’re going to be my readers to the history books.

Beverly Jenkins: Well, you know, that’s great. Oprah always says — how does she say it — anyway, for me, she said something about knowledge is whatever. But for me — knowledge is — I can’t even remember what it is now. But anyway, for me — share knowledge. I mean, if you’ve got knowledge and you’re not sharing it, what good is it. So, for me, shared knowledge and powers is all.

So run to your history books, look up Queen Califia, look up blacks and the 49ers and the Gold Rush, because that’s where I’m setting my book and I’m doing all that history.

Norwood: Thank you, Beverly.

Beverly Jenkins: You’re very, very welcome. Looking forward to seeing you sometime in the future.

You can find out more about the works of Beverly Jenkins at www.beverlyjenkins.net.