Incognizant Racism

May 14, 2010

Washingtonian magazine annually surveys DC’s top doctors, lawyers, and dentists. I was puzzled when its list of top dentists failed to include a single African American in a city 60% Black most of whom patronize Black dentists. Washingtonian is a monthly magazine distributed in the DC area since 1965 described as the magazine Washington lives by, focusing on local feature journalism, guidebook style articles, and real estate advice. It tends to give short shrift to communities of color and particularly the well educated upper middle class African American. An explanation can be found in Don Heider’s book White News: Why Local Programs Don’t Cover People of Color.

Heider studied two news broadcast markets in Honolulu and Albuquerque. African Americans are not the dominant minority but included communities substantially populated with other people of color: Asians, Latinos, and Native Americans. The study was conducted 10 years ago when the white population of Albuquerque was 51% while Honolulu had no racial majority. Heider’s thesis was “to understand how and why certain content does or does not end up on the air in a particular local station’s newscasts” and to understand the process and structure that govern news decisions. He concluded the dominant influences on this process are hegemony and ownership.

The study focused on a newsroom in each market and made the expected observations that top news managers were white males verifying a consistent contention by the U.S. Civil Rights Commission that white males are the gatekeepers of the U.S. media. As a consequence little importannce and coverage are attached to issues involving non-white communities such as, gentrification, affordable housing and displacement, environmental racism, development and education. Workplace diversity was superficial with minority anchors and coverage limited to crime and festivals.

Incognizant Racism, a theory advanced by Philomena Essed in Understanding Everday Racism supports the proposition that hidden under the surface of diversity there is a strong tendency among Whites in the United States to assume superiority of Euro-American values. Hidden also is the expectation that in due time Blacks must accept the norms and values of the Euro-American tradition as superior and that adaptation is the only way to progress in American society. As Heider argues, ownership and day to day practices work together to systematically exclude certain groups thus marginalizing issues important to their communities.

In explaining the process of incognizant racism within the newsroom Heider found some reporters tried to cover relevant issues, some realized more needed to be done, and still others did not even have a level of awareness, yet all worked together to produce a product that consistently excluded stories about entire segments of the viewing audience. The practice results in racist coverage that is a distinctly different kind of coverage of people of color than exists for the White population.

Washingtonian’s claim of presenting the best while excluding significant others lacks credibility. How about calling it what it is: a list of DC’s best white dentists. One solution is certain, minority communities need to own and control their own media outlets and not sell out to corporate conglomerates.

Sanford Roan’s First Round for Diversity

May 7, 2010

In 1939 Sanford Roan made several attempts to integrate the Ohio Highway Patrol. The first African-American applicant brought superior credentials, a graduate of North Carolina A&T with a business degree. He was a star athlete and later a trained pilot with military service. John Bricker an ambitious Ohio gubernatorial candidate urged Roan’s application suggesting the State was eager for an African American patrolman. In a ploy to capture the Black vote Roan unwittingly became a political pawn in Bricker’s election bid.

Ostracized throughout cadet training Roan coped with the humiliating and hostile environment as he would later express to President Roosevelt: “The boys when they would talk to me would make sure no one else was around to see them. Generally, they expressed their sympathy at the conditions, but said there was nothing they could do. I began to realize then that a business or an organization could only be as good as the person or persons controlling them.”

A popular athlete Roan attended a racially mixed high school. Graduating from college into the world of work his race made him a social outcast. Fed up with the treatment he quit the academy. Bricker promptly summoned him and with promises of support and assurances of being in his corner, Roan was persuaded to return. But thing’s grew worse, and again he quit. By then Roan’s difficulties became front page fodder closely followed by Ohio voters. Again in his persuasion this time Bricker promised a political appointment if Roan would only return until after the election. All the while Bricker’s cohort, the Ohio Highway Patrol department’s founder Colonel Lynn Black was determined to keep the force all white and set out to block Roan’s appointment. With a wink and nod from Colonel Black the “Jim Crow” treatment grew more intense. In what was to be routine sparring Roan stepped into a boxing ring surprised in the opposite corner as five white cadets filed in.

Bandaged and brutally beaten Roan submitted his final resignation. The sitting democratic Governor Martin L. Davey promised if re-elected to fire Colonel Black. Bricker promised an investigation. Both candidates only intended to energize the Black vote. Bricker won but his promise for change, an investigation, and a political appointment were quickly forgotten. Roan’s ambition of being a highway patrolman faded.

Bricker too in his ambition would also suffer defeat. The Republican nominee for Vice President of the United States in 1944 shared the unsuccessful ticket with Presidential nominee Thomas Dewey losing to Franklin Roosevelt. Roan might have found some solace in Bricker’s defeat but then Bricker served out his public life in the U.S. Senate. Sanford Roan, the father of Kay and Gary, went on to become a successful businessman in Columbus Ohio.

Sanford Roan was one of those rare men, a courageous pioneer who cleared a path for others. Because of men like Roan who stepped up to a challenge the struggle is no longer about fisticuffs, but continues in the greater goal for diversity. Local Human Rights Commissions now work side-by-side with police departments to overcome past wounds and to open new dialogue towards an inclusive future for all our citizens. Police forces now actively recruit from HBCUs. Sanford Roan’s story clearly illustrates the difficulties of getting to this point.

A Washington Tradition Back to Segregation

April 5, 2010

Last week Eugene Allen died at age 90. The White House butler for 8 presidents from 1952 to 1986 started out as a “pantry man” and dishwasher moving up to Maitre d’. Allen probably took to his grave a host of inside stories of White House goin’ ons, juicey tidbits whispered in confidence among the colored help. No doubt Allen was often an active planner and participant in a White House tradition taking place today, the Easter Egg Roll, the biggest annual White House gathering. He was there when Mamie Eisenhower decided it was time to desegregate the event.

African American children were not allowed inside the White House gates, a tradition dating back to 1878 when Rutherford B. Hayes– the same President who ended Reconstruction–hosted the first White House Easter Egg Roll. Occurring on Easter Sunday a workday for most of Washington’s Black servants who even if possible couldn’t afford to take off and chaperon their children to the public event. Two years later the Smithsonian began what became another tradition believed to be a direct response to the White House practice making African-American children persona non grata.

To this day on Easter Monday D.C.’s children of color still gather at the Smithsonian National Zoo where “ice cream, food and Easter egg hunts await them.” As a child growing up here I remember Washington as a largely segregated city in the 1950s. Like Eugene Allen I’ve seen much change. African Americans coming and going through White House gates are a common occurrence–only now their presence is no longer restricted to the back of the house.

Prestigious Law Firms Scale Back Diversity Recruitment

April 1, 2010

In February, 2009 Yolanda Young filed a discrimination complaint against her former employer Covington & Burling alleging racial discrimination. The firm countered with innuendo calling her an average law student citing her Bar Exam scores as less than outstanding. This despite during her tenure she received a bonus for her outstanding performance. The bar exam tests the minimum competence to practice law. The firm didn’t argue Young’s lack of competence and no wonder, she graduated from Howard University and Georgetown Law; lectured at Vassar College and Louisiana State University; sold her first book (On Our Way To Beautiful) to Random House; provided commentary to NPR and wrote for both The Washington Post and USA Today. Young obviously a high achiever was hired by the firm in February, 2005 as a Staff Attorney. Staff attorneys are the lowest of the pecking order under Partners, Associates, and Special Counsel and are rarely promoted onto the partnership track. Young spoke out writing a piece published in U.S.Today exposing the firm’s practice of concentrating minorities at the bottom rung. Subsequently Young alleged management began a clandestine campaign of harassment and discrimination ending in termination.

Young’s experience doesn’t come as news to most African American lawyers who came out of law school long before her. The legacy of gifted Black attorneys none of whom made their mark in America’s prestigious law firms: Thurgood Marshall, Constance Baker Motley, William Henry Hastie and Charles Hamilton Houston and many other great African American legal minds were excluded from the top firms but rose to prominence as judges, civil rights leaders, politicians and academicians.

As minorities and particularly African Americans increasingly move into the executive ranks of corporate America, the prestigious law firms have been slow to follow. Firms like C&B play statistical card tricks creating an illusion of diversity while a closer inspection reveals minorities concentrated in low level positions that offer little or no opportunity for advancement.

The Diversity Scorecard has a adopted a new methodology to address the card tricks by no longer looking at the overall percentage of minorities within a firm but also focusing on the partnerships ranks and the breakdown of the various minorities. The figures in the 2010 Scorecard reflects the larger labor market with African Americans losing ground with law firms. The data shows a strong correlation between firms that drastically cut overall head count and firms that saw significant losses of minority lawyers. Blacks are long familiar with the last hired first fired.

Change starts at the top. The top of the legal profession while giving lip service has pretty much resisted change. We know that as the world becomes more multicultural the more important it is for law firms to rise and meet the challenge. Where you have people from different backgrounds you get different perspectives, more ideas, new ways of thinking about things, and more opportunities for problem solving.

Young eventually abandoned her suit. I can imagine why. Being treated badly by an employer for whom you gave your best can be a painful experience you’re forced to revisit constantly through litigation. It’s not worth the cost both financially and emotionally. Sometimes it’s easier to just let it go, forgive, and move on. I give praise to Yolanda Young for pointing out the errors of Covington and Burling’s way.

Taboo the Issue of Race

March 24, 2010

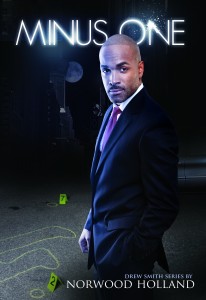

Growing up in the South and being amongst the first generation to integrate public schools I’ve always noticed how discussions of race with whites can cause discomfort–a subject many would rather not engage. It was one such discussion that prompted this blog. I pitched a story to Sheri Dalphonse Editor of the Washingtonian magazine on an local African American filmmaker and his efforts to turn his award winning short into a feature film. I got the idea after reading a similar story in the prior editon about similar efforts of two white male filmmakers. The editor rejected the pitch. I questioned why white filmmakers merited coverage but the African-American did not. Offended she declared race had nothing to do with it. I left it that. Months later I pitched another story about and a remarkable artist and ex-con that almost made it into print. I sensed her lack enthusiasm believing the subject would not interest Washingtonian’s upper crust white audience.

I knew the risk of raising race and offending the editor would not help getting me into print, but I couldn’t let it go. A year later the Washingtonian ran an article on the top 100 dentist in the Washington area–all white. The editor claimed the survey method was unbiased relying on the local dentist and members of the American Dental Association. I raised the fact that Washington DC was 60 percent black and most black folk patronize black dentists. I questioned why no black dentists were represented at the top. Again, I had offended but the offense gave serious pause for thought, qualifications and patient satisfaction were not determinative.

I let her know that her survey was biased because she neglected to contact any dentist in the National Dental Association. Huh? Unaware the African American dental profession like the medical and legal professions as a result of a history of discrimination had formed their own professional associations, a time honored tradition. The editor had in fact unintentionally discriminated. I had enlightened her and she promised to include the National Dental Association in the next annual survey. I also noticed the magazine has since hired an African American staff writer a former local TV news reporter.

By confronting the taboo I raised the Editors conscience and paved a way for the opportunity of another. The Washingtonian may never publish any my work because of my ethnic outlook, but they’ll think twice about excluding ethnic content in the future. The Washington community is made up of Asians, Latinos, Blacks and others. It’s important to engage discussion on race and ethnicity no matter how uncomfortable—it just good business. A history of opportunity denied by countless editors caused a certain self-reliance. I have herein made my own.